Written under the supervision of PhDr. Soňa Nováková, CSc, M.A., and submitted on 14 January 2011, this essay was part of my total coursework at the Department of Anglophone Literatures and Cultures at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts. The essay is published with the kind permission of the faculty.

Disguise in The Merchant of Venice and Volpone

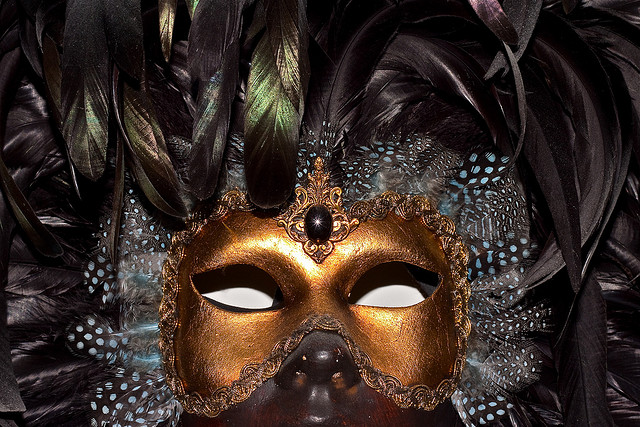

Androgyno brought up a curious question when he exclaimed that he would not prefer to have only one sex, that he would like to stay both a man and a woman, but not at all only for the sake of generating humor by the obvious duplicity. As far as he was concerned, the reason for using such a disguise was not to “be stale and forsaken” (Volpone I, i, 55). Disguises of various natures, or more particularly cross-dressing, were indeed a marvelous idea and a great theatrical practice. However, it must have soon occurred to the playwrights that cross-dressing characters merely for the sake of having fun by watching others’ confusion was rather simplistic. Luckily for both the audiences and the playwrights themselves, there are much more types of disguise to choose from than only the aforementioned cross-dressing. This essay deals with the various forms of disguise, be it seemingly simple cases of cross-dressing, plays of pretend, or even mere linguistic masks, in William Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice” and Ben Jonson’s “Volpone, or the Fox”.

The question first and foremost to be raised is: What do we understand by the word “disguise”? Taking the meaning broadly, we may argue that disguising oneself is essentially pretending to be something or someone else, pretending to be what one is not. For instance, for all of the casket scenes in “The Merchant of Venice” the theme of disguise is utterly crucial. All three suitors know that “all that glisters is not gold” (The Merchant of Venice II, vii, 65) but only one of them is able to fully realize the whole extent of the meaning of this phrase. Morocco at first persuades Portia that the shade of his skin has nothing to do with who he really is only to later on judge the golden casket solely by its outer appearance. Arragon initially chides the “fool multitude that choose by show” (The Merchant of Venice II, ix, 25) but eventually makes the very same mistake he has been taking such a firm stand against. Only Bassanio is capable of making the right decision, of not judging the book by its cover, of not being misled by the outer appearance but seeing behind it. In spite of the possibility to use the casket scene as an exemplary case of the importance of disguise in both plays, however, is only one of the many cases in point. There are many others left to be revealed.

“Differences between the sexes [find] expression in distinctions of habit and convention with regard to dress” (Bauer, 40), and on the Elizabethan stage, populated solely by boys or men, cross-dressing was the only applicable way of bringing some femininity onto it. Playwrights frequently had their female characters dressing up as men, and vice versa. The first case, in particular, seems to have been particularly favorite one, perhaps because “self-aware, skillful women seem to have been both alluring and threatening to Shakespeare and his audiences” (Berek). Nevertheless, the playwrights did not use this dramatic tool only for the sake of comedy. The characters had to have another, more important reason for their doings. Even though we only have a couple of instances of cross-dressing in “The Merchant of Venice” and “Volpone, or the Fox”, all of them have a different function, and all of the characters take a different stand to it.

Let us begin with Jessica from “The Merchant of Venice”. She not only dresses herself up in a page clothes in order to leave her house and flee from the town unseen, she may also do so in order to avoid any unpleasant confusion. After all, in a town like Venice, known for its courtesans and at the time in the middle of carnival merriment, a single lady on her way through the streets accompanied by a couple of men might put her in a rather bad light. In spite of her disguise being justifiable, however, Jessica is far from being satisfied with it. In fact, she is “much ashamed of [her] exchange” (The Merchant of Venice II, vi, 35), but her reasoning for that is unclear. Generally speaking, should a woman at that time disguise herself as a man, she would actually rise up on the social ladder. Following that logic, Jessica should not have any reason for complaining. Unless she was ashamed of obscuring her good looks, which would inevitably make her rather shallow and vain. Shakespeare, of course, does not give us any direct answer for this dilemma, so we can only guess and decide on our own.

The reason why Portia and Nerissa disguise themselves in male clothes is even more pragmatic. Judging from the absence of any women in the trial scene it appears that they were not even let into the courtroom, let alone to be allowed to embody such a crucial role. As opposed to Jessica, however, these two ladies seem genuinely enthusiastic about their transformation. In her speech, Portia joyfully enumerates a couple of the “thousand raw tricks of [all those] bragging Jacks” (The Merchant of Venice III, iv, 77) whose behavior she is to imitate. Portia, after all, does not have any reason to be ashamed of her disguise. As a wealthy lady, she has to be accustomed to masques and celebrations (Coles, 48), and as a strong, secured female character she does not need to feel the necessity to be ashamed in any form she takes on. It appears, however, that Portia enjoys the power her disguise provides her with a bit too much (Hilský, 203). She toys with Shylock in the trial scene, pushes him ever further, and prevents him from killing Antonio only at the very last moment, not caring for how cruel she is towards Bassanio and Antonio himself. Of course, her actions are not entirely unjustifiable. Not recognizing his wife, Bassanio admits in front of her that he would rather have her dead than to lose his friend. Perhaps, Portia was just trying to have her piece of revenge – but she does not seem to be a vengeful person to begin with, and even if she was, the ring trick in the fifth act would certainly have sufficed. Perhaps, then, she was simply attempting to show Shylock’s cruelty – but everybody already knew about this heinous characteristic of his. Shakespeare, once again, does not provide a clear answer. Through the character of Portia, he merely appears to examine the possibilities of cross-dressing on stage (Hilský, 200).

The least important case of alleged cross-dressing is to be found in “Volpone”. In one of her scenes, Lady Would-Be accuses her husband of having an affair with a female prostitute disguised as a man. Not realizing her mistake, she scolds the poor young man, a friend of her husband’s. Unlike in Shakespeare, however, the theme of cross-dressing is in this very short scene used solely for comical purposes.

Volpone disguising himself as a dying old man, a mountebank, or a commandatore, might be considered a fringe case of cross-dressing, not in any way related to the actual change of sex. It is used in the play largely for comical purposes – or at least the main character seems to enjoy deceiving others. In this sense, his attitude towards disguises is much closer to that of Portia and Nerissa, than that of Jessica. Volpone’s disguises are also a great source of dramatic irony since the audiences know that he is not actually dying, or selling a miraculous cure, or being dead already for that matter. Firstly, deceiving the three men into thinking he is dying, Volpone actually causes himself to “forfeit the pleasures of health […], which finally forces him into a kind of living death” (Hawkins). Volpone has to stay in his role, and due to numerous interruptions he is never really able to fully enjoy the fruits of his deceptions. Secondly, disguised as a mountebank, Volpone creates yet another source of dramatic irony. “The very physical appearance of the mountebank and his helper contradict the claims they make for their medicine” (Hawkins). However, accurateness of his mountebank disguise was never a number one priority for Volpone. He merely wanted to see Celia, and have fun in the process. In this sense, he succeeded – he saw and fell in love, or rather lust, with Celia and, as he afterwards joyfully confesses, he “did it well” (Volpone II, ii, 31). It is only with his final disguise, which he intended to use in a humorous way as a means of mocking and torturing the three men, who thought they would inherit his whole wealth but were eventually to be disappointed, that Volpone realizes he “ne’re was in dislike with [his] disguise,/Till [that] fled moment” (Volpone V, i, 2-3). His servant, and friend, is soon to betray him, and Volpone himself is to lose everything and be sent to prison. The buoyant comedy grows bitter.

Apart from cross-dressing, the most visible of the various disguises, there is also a vast amount of simple pretending in both plays. Many characters rather frequently pretend to be something or someone they obviously are not. It can be a mere mention – like Portia claiming to Bassanio that she is but “an unlessoned girl, unschooled, unpracticed” (The Merchant of Venice III, ii, 159), when, in an actual fact, she is one of the most, if not the most, intelligent characters in the play. It can also be only one or two scenes – Mr. Would-Be teaching how to pretend to be a good politician, Volpone’s three “suitors” pretending to care for nothing less than his full recovery, Voltore claiming at the court to be nothing short of a saint and transferring all the guilt onto the innocent ones, only to eventually pretend to have been possessed by the devil the whole time, or Lancelot Gobbo pretending not to be his father’s son and making fun of the poor old man’s perplexity. What should we, as readers or audiences, think about such an amount of unpredictable pretending? We may certainly feel insecure at times about who is pretending to be who, and for what reason. We may not know what to expect next. Saying that, we may come to a realization that this might in fact be what the playwrights were exactly aiming for – surpassing people’s expectations, surprising them and making them constantly entertained.

Nevertheless, the play of pretend also has in both plays somewhat more static and reliable examples, characters whose pretences, or intricacies, are subtly spread throughout the whole text – Mosca and Bassanio. Throughout the whole play, Mosca pretends to be Volpone’s faithful servant, to be merely a “poor observer” (Volpone I, i, 63) of his, and successfully makes Volpone believe he is no parasite – in spite of his openly admitting the very fact in act three, where he claims that being a parasite is “a most precious thing, dropped from above” ()Volpone III, i, 8. In spite of all that, every time he gets a chance, Mosca makes sure he has an escape plan in case of Volpone’s finding out about his true intentions. He manages to befriend all of the three men Volpone plays his tricks on, and indebt them to him so that if anything should happen to his current master, he could go into their service. This mask of his is torn off only at the very end of the play by Volpone himself, who is unwilling to be blackmailed by him, and sacrifice more than half of his possessions to him. The fact that he is since the very beginning such a fair weather friend in a way anticipates Mosca’s final betrayal of Volpone. Thus, the audiences may, to a certain extent, foresee where the play might be going, stay with the plot and not get confused or lost.

As far as Bassanio’s play of pretend is concerned, we have to admit he is a man of paradoxes. In the very beginning of the play, he admits to Antonio that he has no money, that he is essentially a nobody, which is also the reason of his dire need to borrow from his friend. However, when talking about Bassanio’s visit to Belmont, Nerissa mentions him as “a scholar and a soldier” (The Merchant of Venice I, ii, 108). Does that make him a liar? Technically yes for, indeed, he made Portia believe that he is much better-off, and that he stands socially much higher than what is the reality. Admitting that, we also have to realize that he had no other choice. Considering his feelings towards Portia are honest, considering he truly loves her, he would have been desperate to get to her, and pretending to be an important person of great renown and wealth would be his only chance to actually meet her. In unison with his pretending, Bassanio, during the casket scene, talks about the “outward shows” sometimes being “least themselves”. In this scene he attacks everything that is beautiful on the outside but hides a hideous inside. Like his beautiful speech against the false beauty, Bassanio pretends on the outside to be someone vastly different than who he is on the inside. Liar he is then, after all, but since he only becomes one in order to woo his beloved Portia, we may say that he is basically a liar for the good.

The last case of disguise we are to talk about is the linguistic one. On a few occasions, the characters use different language to disguise themselves, or to reach their goals. This is particularly to be seen in “Volpone”. When disguised as a mountebank, Volpone makes a sudden switch into prose, and uses much more colloquial language in order not to be recognized by anyone in the crowd. Also, when attempting to woo Celia, he changes his register and suddenly starts using an amorous lovers’ language to make her make love with him. Lovers’ language is also atypically used by the extremely jealous Corvino when he, immediately after calling his wife a prostitute, tries to persuade her to give herself to Volpone. These abrupt changes in the way the characters speak, these verbal disguises they take on, make them effectively unreliable. They pretend and deceive using the language, therefore should under no circumstances be trusted. Even though Johnson uses this form of disguise mainly for comical reasons, there is always a glimpse of cruel mischief in them, a sense of a vague threat.

Interestingly enough, we would not find as many cases of this linguistic disguise in “The Merchant of Venice” as we did in “Volpone”. Only Shylock appears to say much more than what the words he pronounces actually mean (Hilský, 180). The reason for Shakespeare not using this rhetorical switch may be that there is simply no need for. Portia, the only character who is given enough space to be able to make use of any sort of linguistic disguise, does not even attempt to do so. After all, she is pretending to be a highly-educated lawyer so, for instance, any form of vernacular would not only make her not credible at court, it would more importantly be utterly out of place.

To conclude, there are many forms of disguises in “Volpone, or the Fox” and “The Merchant of Venice”, tiny and seemingly insignificant ones on one hand, and immense and extremely important ones on the other. These disguises generate numerous cases of dramatic irony and lead to countless misunderstandings but, most importantly, are highly entertaining to watch in the theatre or read in the book. They make us think about what we ourselves do and how we behave. They make us not take anything for granted. In real life, very little things are exactly what they at first appear to be, and in this sense, both plays provide their audiences and readers with an accurate and much entertaining mirror to the reality.

Bibliography:

Primary texts:

Bejblík, Alois, Jaroslav Hornát, and Milan Lukeš. Alžbětinské divadlo” Shakespearovi současníci. Praha: Odeon, 1980.

Jonson, Ben. Three Comedies. London: Penguin, 1966.

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Translated by Martin Hilský. Brno: Atlantic, 2005.

Secondary sources:

Bauer, Heike. Women and Cross-Dressing: 1800 – 1939. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Berek, Peter. “Cross-Dressing, Gender, and Absolutism in the Beaumont and Fletcher Plays.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. Vol. 44, No. 2. Spring, 2004. Accessed on <www.jstor.org>

Coles editorial board. Shakespeare: The Merchant of Venice: Review questions and answers. Toronto: Coles Publishing Company, 1984.

Hawkins, Harriet. “Folly, Incurable Diseases, and Volpone.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. Vol. 8, No. 2. Spring, 1968. Accessed on <www.jstor.org>

Hilský, Martin. Shakespeare a jeviště svět. Praha: Academia, 2010.

Pearson, Jacqueline. The Review of English Studies, New Series. Vol. 48, No. 190. May, 1997. Accessed on <www.jstor.org>

Napsat komentář