Written under the supervision of Prof. David L. Robbins and submitted on 19 September 2011, this essay was part of my total coursework at the Department of Anglophone Literatures and Cultures at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts. The essay is published with the kind permission of the faculty.

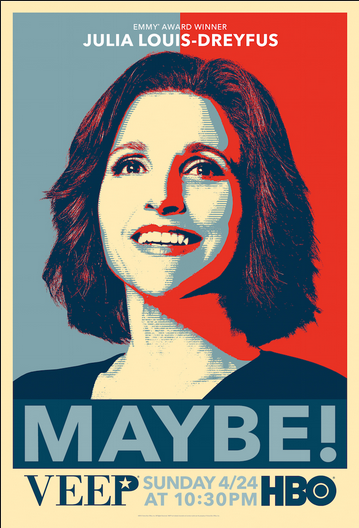

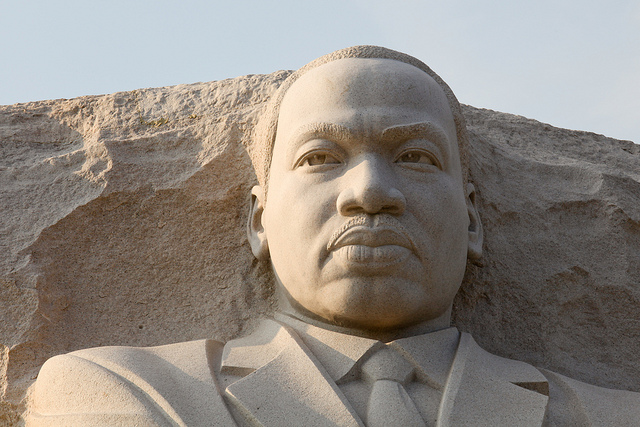

Contrasting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X

In the eyes of many, there are no better examples of two people standing on the opposite sides of a spectrum of any sort than Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Even though they are both remembered as avid champions of civil rights, individually they took very different approaches as to how to reach their common goal. Whereas the first one is in our minds associated with peaceful thoughtfulness, the latter one is generally thought of as a violent brute filled with nothing but hatred and rage. While it would be all too easy to simply praise the first and condemn the latter, it is essential that we submerge a little deeper into the issue and attempt to uncover and explain what made them so different and yet, in many aspects, also indisputably similar. This essay will discuss the similarities and contrasts between the two most prominent personalities of the American Civil Rights Movement – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X – as evidenced primarily in Dr. King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and his I Have a Dream speech, and Malcolm X’s Message to the Grass Roots and The Ballot or the Bullet. It will attempt to prove as well that even though Martin Luther King and Malcolm X are for many of us perfect examples of a “study in polarity” (StudyWorld) who have absolutely nothing in common, they are, in an actual fact, far more comparable to two sides of the very same coin.

Let us begin by focusing on the most prominent evidence of their similarities and/or differences which may be found in the written and spoken records the two men have left us – their varying literary styles. If we take a look at Letter from Birmingham Jail and The Ballot or the Bullet, we notice the difference in their styles already in the initial addressing. Whereas Dr. King opts for a rather formal and reserved “my dear fellow clergymen” (Letter from Birmingham Jail) which, in spite of being a perfectly adequate address for the given situation, is somehow no more than that, X opens up his speech saying “Mr. moderator, Brother Lomax, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies” (The Ballot or the Bullet), which is not only suitable as well, but also proves to be much more universal, heartfelt and therefore further-reaching. While Dr. King seems to keep his distance a bit from the very beginning, Malcolm X is not shy to reach out to everyone in particular, thus creating a personal bond between himself and every single individual who might be listening to him.

The same difference – the formality of King’s style in opposition to X’s laid-back casualness of expression – is reflected in the choice of vocabulary and their syntax as well. On one hand, Dr. King proves to be an exceptionally well-educated man with a wide vocabulary and a great grasp of the English language who, on top of that, is not ready to simplify his ideas merely for the sake of their easier comprehensibility. He must have had faith that even though the less educated may not understand every single word he had used, his ideas were universally understandable and that their transmission would thus not prove to be such a problem. Following the same logic, his syntax is often times rather convoluted, boasting interesting and striking imagery, albeit at times highly demanding of our attention. Malcolm X, on the other hand, goes in a different direction with the language he uses. Attempting to be closer to the poorly educated lower classes from which he himself once originated, his vocabulary is simple, his syntax straightforward, and his ideas easily transmittable. Once using the word “reciprocal” in his speech, he immediately draws attention to it, explaining to the audience: “I don’t usually deal with those big words because I don’t usually deal with big people. I deal with small people” (The Ballot or the Bullet).

One similarity that we may find in both King’s and X’s writing styles is the heavy use of repetition, be it a repetition of words, sentences, or whole ideas. In this respect, according to Wesley E. Mott, King (and effectually also X) draws on the “traditional Negro sermon” (Mott, 412). This type of sermon is based on a formulaic method which employs precisely such devices as “repetitive refrains, recurrent rhetorical questions, and formalized dialogue and narrative” (Mott, 412). The predominant reason for using repetition in a speech is obvious – repeating what has been said puts an additional emphasis on the issue as well as makes it far easier to remember.

Yet another instrument which aids to get the message across and which both men employ is the use of slogans. What is meant by that are short sentences containing powerful messages which have the potentiality of becoming universal mottos for their particular causes. In case of Dr. King we may draw attention to: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” (Letter from Birmingham Jail), and in that of Malcolm X to: “I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare” (The Ballot or the Bullet). These hard-hitting statements have the power in them to easily get under one’s skin. They are simple to remember and have a long-lasting effect which must have been a reason in itself for them to have been used.

Additionally, in their writing styles, each of these two men uses another strategy altogether to captivate the attention of their audiences and to gain their goodwill. In case of Malcolm X it is humor that he uses to get the people on his side, albeit a very dark humor. When making a point about the unbearable social situation in the individual states of the US, he quips: “[…] Texas is a lynch state. It is in the same breath as Mississippi, no different; only they lynch you in Texas with a Texas accent and lynch you in Mississippi with a Mississippi accent” (The Ballot or the Bullet). Even though the joke is rather grim, it is a joke nonetheless. Its function is to lighten up the mood among the people, perhaps in order to make the speaker more agreeable and thus, although it may seem like a little bit of a stretch, trustworthy. Martin Luther King uses a different tool – he leans on the authorities not only from the Bible but also from elsewhere. Citing these authorities – Moses, Socrates, Lincoln, Jefferson, Aquinas, St. Augustine, and Nebuchadnezzar, to name a few – has an incredible verbal impact for “the very weight of his authorities assuages a reluctant audience’s fears that his actions are frighteningly without precedent” (Mott, 416).

Taking a step back from their writing styles we will immediately start seeing patterns spread throughout the bodies of their work. These patterns in many cases overlap and thus we find that King and X had a lot in common. At the same time, however, we may begin to spot the main differences between the two men as well as the possible explanations for them. Let us begin with what the two had in common.

One of the first feelings by which a reader is stricken upon listening to or reading the I Have a Dream speech or The Ballot or the Bullet is the sense of great urgency, of actions needed to be done immediately. Dr. King reminds “America of the fierce urgency of Now” (I Have a Dream) while Malcolm X warns that “the black nationalists aren’t going to wait” (The Ballot or the Bullet). It is clear that the situation has reached the point when there is simply no more time for waiting, postponing the solution, or hoping that it will solve itself somehow someday. Particularly in the 1960’s “radical voices were becoming increasingly popular” (Umoja, 564) and the young African-Americans were getting ever more frustrated and militant (Umoja, 560). Both King and X were receptive to the heat of the situation but while the first one tried to calm people down and thus avoid unnecessary violence, the latter one was only adding the heat, hoping for some actions, albeit potentially drastic, to be finally taken.

In unison with the urgency to act, the necessity to unite also permeates both King’s and X’s bodies of work. The issue, however, is not as simple as it may sound. Whereas King stated that “the marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people” (I Have a Dream) and therefore, as far as he was concerned, all people were in this fight together, no matter what the tone of their skin was, in case of Malcolm X there always seems to be two groups among the population, distinguished by the color of their skin. On one hand, X advises that we must “learn to forget our differences” (Message to the Grass Roots) but this clearly applies to African-Americans only for “the white man [is] an enemy to all of us” (Message to the Grass Roots). In his dark and pessimistic mind, X could have never even imagined a society where there would be no distinction between the members of each race, where the color of one’s skin simply would not matter. King, however, was hopeful that the day would come when all people would have the same rights, and so he did not condemn Caucasians. Instead, he seems to have distinguished between the people who fought for the good cause, for equality and freedom – be they black or white – and those who were not yet convinced of the advantages of such state.

Also, familiarizing with the speeches and texts one is struck by the emotionality of them, by the level of their authors being personally affected by the issue at hand. For instance, in the beginning of I Have a Dream, King gives a sigh that even a hundred years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, “the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land” (I Have a Dream). Malcolm X admits to a similar sense of uprooting in The Ballot or the Bullet, claiming: “Everything that came out of Europe, every blue-eyed thing, is already an American. As long as you and I have been over here, we aren’t Americans yet” (The Ballot or the Bullet). The difference between the two seems to be that while King uses the scarce emotional passages to commiserate with the audiences and to build an argument, X merely tries to well up a feeling of rage in them, aggravate them so that they would become more compliant to his cause. We can clearly see that in his Message to the Grass Roots where, after a long passage on revolutions and bloodshed, he rather unnecessarily continues by invoking vivid images in his audience of “your churches […] being bombed, and your little girls […] being murdered” (Message to the Grass Roots). Mott addresses the same issue with reference to Letter from Birmingham Jail, writing: “King’s stance does not hide his rage [but by] suppressing his personal anger and frustration, and by resisting the human impulse to bombast and diatribe, he has […] achieved a compelling piece of polemic” (Mott, 414).

Other emotions that are directly alluded to by both King and X are disappointment and a sense of betrayal. “As in so many past experiences, our hopes had been blasted, and the shadow of deep disappointment settled upon us” (Letter from Birmingham Jail) says Dr. King, having the white moderates as well as the white clergy in mind, as Malcolm X talks about “the white political crooks […] with their false promises which they don’t intend to keep” (The Ballot or the Bullet). While some of us might have felt despairingly listless when faced with such situation, King and X took different approaches in accordance to their view of the state of humanity and the world. King remained hopeful, feeling that “you are men of genuine good will” (Letter from Birmingham Jail) and that “we will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom” (Letter from Birmingham Jail), while X, having lost all hope, menaced that all these dissatisfactions “can only lead to one thing, an explosion” (The Ballot or the Bullet).

However, the reason we remember Martin Luther King and Malcolm X together is because of their greatest difference – their position to violence as a course of action in the Civil Rights Movement. Along with Gandhi, after whom he partially modeled himself, Martin Luther King is the most prominent advocate of non-violence. Essentially, he realized that in the modern society, radicalism and violence are not the best way to achieve one’s goals, and that a patient negotiation and peaceful protesting are much more powerful instruments of change, albeit their efficacy may prove to be long-term rather than immediate. Stating that, we might consider Malcolm X as King’s direct antagonist – professor of radicalism and of treating violence with violence. Nevertheless, X seems to have been very careful not to promote violence on people directly, at all times moving through the realm of vagueness, giving statements such as: “I believe in action on all fronts by whatever means necessary” (The Ballot or the Bullet). In one of the most memorable passages in The Ballot or the Bullet, X masterfully tiptoes right around the edges of the point of no return: “It is constitutionally legal to own a shotgun or a rifle. This doesn’t mean you’re going to get a rifle, form battalions and go out looking for white folks, although you’d be within your rights – I mean, you’d be justified; but that would be illegal and we don’t do anything illegal” (The Ballot or the Bullet). It is only the fact that he expresses that idea out loud – even though he officially discourages anyone from actually putting that idea in action – that seems sinister and malevolent. He clearly knows what he is implying but makes sure he can be in no way legally punishable should any bloodshed follow. In this light, it is very difficult to believe him when he says that he is “nonviolent with those who are nonviolent with [him]” (The Ballot or the Bullet). It is precisely this dangerous approach of Malcolm X and the Black Nationalist Movement, the member of which X was for a long time, which King has in mind when he talks about the force “of bitterness and hatred [which] comes perilously close to advocating violence” (Letter from Birmingham Jail).

As it was already mentioned, Dr. King was an avid supporter of the non-violent direct action when fighting for the civil rights and that was even though there is an inherent paradox in this approach of which King was well aware. In spite of the immorality of violence, he knew that his nonviolent methods were most successful when they provoked violence from the side of the oppressors (Colaiaco, 7). Of course, King always hoped to achieve his goals without a drop of blood spilt but “because the racist community was usually unyielding, civil rights activists found that when they used soul force, they were often met by physical force” (Colaiaco, 7-8). In his autobiography, Malcolm X describes these sorts of endeavors as “nonviolent marching that dramatizes the brutality and the evil of the white man against defenseless blacks” (Haley, 377) essentially deeming them foolish. It is interesting, though, that in spite of this he has enough respect for King not to deny him his doctorate, referring to him all this time as “Dr. Martin Luther King”.

At this point, it is time to ask an important question: How come that the two men who fought for the same cause could take approaches so radically different? The most probable explanation may be drawn from their background, the world in which they lived over the course of their childhood and young adulthood. Whereas Dr. King was raised in a comfortable and loving middle-class family, Malcolm X came from an underprivileged home, his father frequently beating his mother before being killed by a group of Klansmen (StudyWorld). His mother, consequently unable to take care of the family, suffered a nervous breakdown, and Malcolm had to be transferred to a foster care (StudyWorld). It is then not so surprising that he has grown a potent sense of distrust, rage and spite within himself, and that for most of his life he may have yearned for revenge. The very first sentences of his highly praised Autobiography indicates what was on the top of his mind all the time, from what he could never escape: “When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders galloped up to our home in Omaha, Nebraska, one night. Surrounding the house, brandishing their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out” (Haley, 1). The whole scene, however, appears to be more frightening than aggravating and it is precisely fear that may be the key term here. As Dr. King said: “Hatred and bitterness can never cure the disease of fear” (King, 77). We may argue that at the root of Malcolm X’s malevolence was fear, lodged deeply inside of him, fear of the white man. He would never show it, or course – no man ever does – and instead would rather hide it a little bit deeper every time he could, and repress it. It almost seems, then, that it was exactly Malcolm X that Dr. King was talking about when he wrote in his Letter from Birmingham Jail: “If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence” (Letter from Birmingham Jail). This, therefore, begs a question: Should we rather condemn Malcolm X for what he stood for or pity him for what had been done to him?

Presently, we have to realize, though, that not only Malcolm X was in the picture and knew about the alarming state of the African-Americans in the society. Dr. King was also well aware of all the atrocities that were happening to them on a daily basis. He has also seen “vicious mobs lynch your mothers, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters” (Letter from Birmingham Jail), but the difference between him and X is that he has simply “seen too much hate to want to hate, myself, and I have seen hate on the faces of too many sheriffs, too many White Citizens Councilors, and too many Klansmen of the South to want to hate, myself” (King, 58). Thus, we once again learn that while Malcolm X has positively lost all hope, Martin Luther King kept believing that humanity has a chance and was not ready to come to hate it.

Another potential reason for Malcolm X’s inclination towards violence might be his religion, or at least his understanding of Islam. If we take a look at Martin Luther King and Christianity, we may understand them as standing on the opposite side of the spectrum. Throughout the body of his work, King often mentions the nonviolent, pristine “vision of Christian perfection” (Mott, 418), believing that “Christianity must actively promote social justice” (Colaiaco, 15), X’s understanding of Islam, however, is much more prone to violence. In Message to the Grass Roots, Malcolm X addresses this issue directly, stating that “there is nothing in our book, the Koran, that teaches us to suffer peacefully. Our religion teaches us to be intelligent. […] If someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery” (Message to the Grass Roots). This statement goes hand in hand with the critical beliefs of a contemporary American political commentator, Bill Maher. In his show on HBO called Real Time with Bill Maher, he at times discusses topics involving the Muslim world, including the comparison of Christianity and Islam, and of Christian and Muslim fanatic believers. In one of his interviews, he called Koran a “hate-filled holy book” (Bill Maher to Muslim Rep. Keith Ellison: The Qur’an is a ‘Hate-Filled Holy Book’) and claimed that it is taken too literally by some of its extreme followers, whom he compared to the Christian extremists as following: “When it comes to […] religions, extreme Muslims are like Godzilla, and we’re like Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret” (Bill Maher on Islam and the South Park ‘Muhammad Bear Suit’ Controversy). Malcolm X may be viewed exactly as an extremist, taking the more spiteful parts of the book too literally, while all that time overlooking the parts of the text which discuss the importance of love, peace and unity. It may only be arguable whether X converted to Islam because he thought it would be a good outlet for his rage, or whether he was not aware of that potentiality of this religion, and only discovered and made use of it when he was in. Be that as it may, it seems that he has found a perfect match.

In conclusion, it is fundamental to realize that Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were not as antithetical and different than some would think. Even though they could never find a common ground on the issue of violence, we can imagine them as two sides of the same coin. Even more so because it is clear that towards the end of their lives they became more similar to one another than either of them could have ever imagined. Whereas Malcolm X appeased his raging mind, broke with the Black Muslim movement, and began stressing the importance of black pride and self-respect over hatred and revenge, Dr. King became frustrated with the slow development of the situation of African-Americans, of the ineffectuality of his nonviolent method, and so he started promoting nonviolent sabotage (StudyWorld). It is a shame that neither of them lived long enough to see the world of today, the world of ever growing tolerance, the world they so diligently fought for. It is a shame because both of them would deserve it.

Bibliography:

Primary texts:

King, Martin Luther. “I Have a Dream.” American Rhetoric. 21 August 2011. 15 September 2011 <http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm>

King, Martin Luther. “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” MLK online. 15 September 2011. 15 September 2011 <http://www.mlkonline.net/jail.html>

X, Malcolm. “Message to the Grass Roots.” TeachingAmericanHistory. 15 September 2011. 15 September 2011 <http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1145>

X, Malcolm. “The Ballot or the Bullet.” Social Justice Speeches. 15 September 2011. 15 September 2011 <http://www.edchange.org/multicultural/speeches/malcolm_x_ballot.html>

Secondary sources:

“Bill Maher on Islam and the South Park ‘Muhammad Bear Suit’ Controversy.” Youtube. 15 September 2011. 15 September 2011 <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RUEaMA4gRIk>

„Bill Maher to Muslim Rep. Keith Ellison: The Qur’an is a ‘Hate-Filled Holy Book’.” Youtube. 15 September 2011. 15 September 2011 <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mVTK_XffAvk>

Colaiaco, James A.“The American Dream Unfulfilled: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Phylon 1st Qtr. 1984: 1-18.

Haley, Alex and Malcolm X. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Ballantine Books, 1964.

King, Coretta Scott. The Words of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York: Newmarket Press, 1983.

“Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.” Studyworld. 23 April 2010. 15 September 2011

<http://www.studyworld.com/newsite/reportessay/Biography/HistoricalFigures%5CMartin_Luther_King_Jr__and_Malcolm_X-9233129.html>

Mott, Wesley T. “The Rhetoric of Martin Luther King, Jr.: Letter from Birmingham Jail.“ Phylon 4th Qtr. 1975: 411-421.

Umoja, Akinyele O. “The Ballot and the Bullet: A Comparative Analysis of Armed Resistance in the Civil Rights Movement.” Journal of Black Studies March 1999: 558-578.

Napsat komentář